Drilling into the Ditiano in search of the Pre-Hellene Floodplain

More drilling to occur in summer 2022

Ashlar walls show us what is impossible for one is accomplishable through cooperation.

The Race Horse Plastic, from Kempton Excavations

Ongoing Research

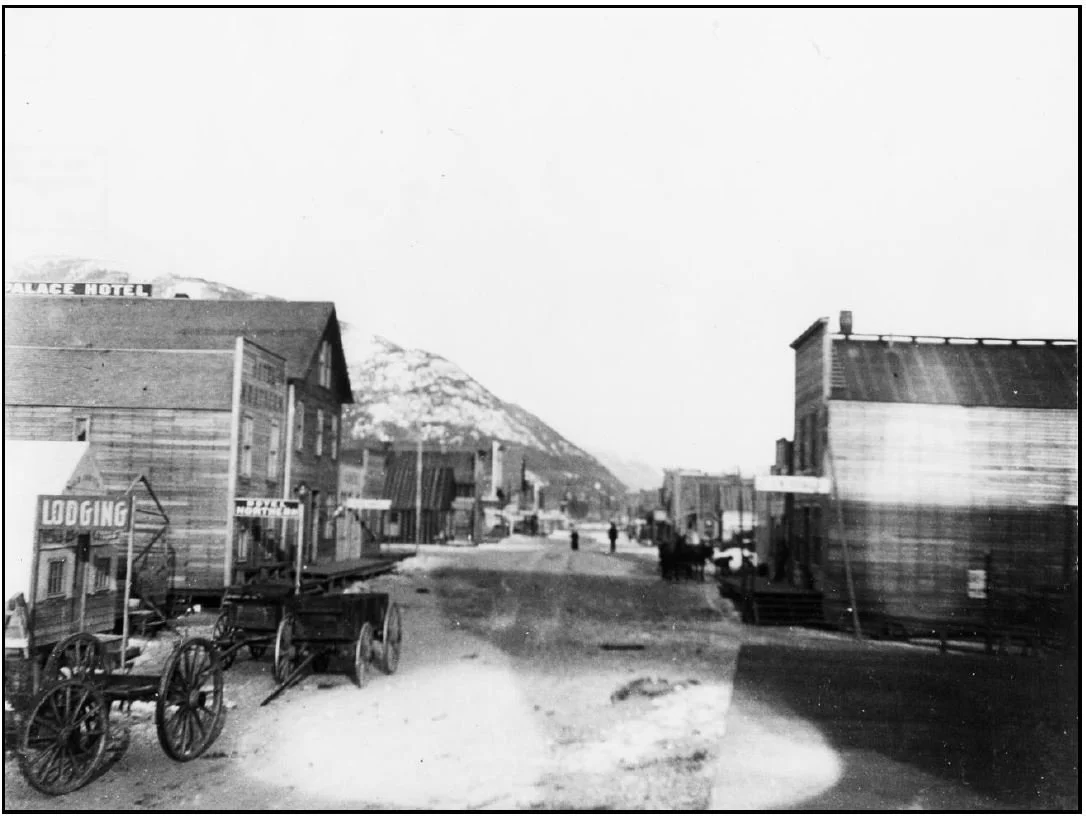

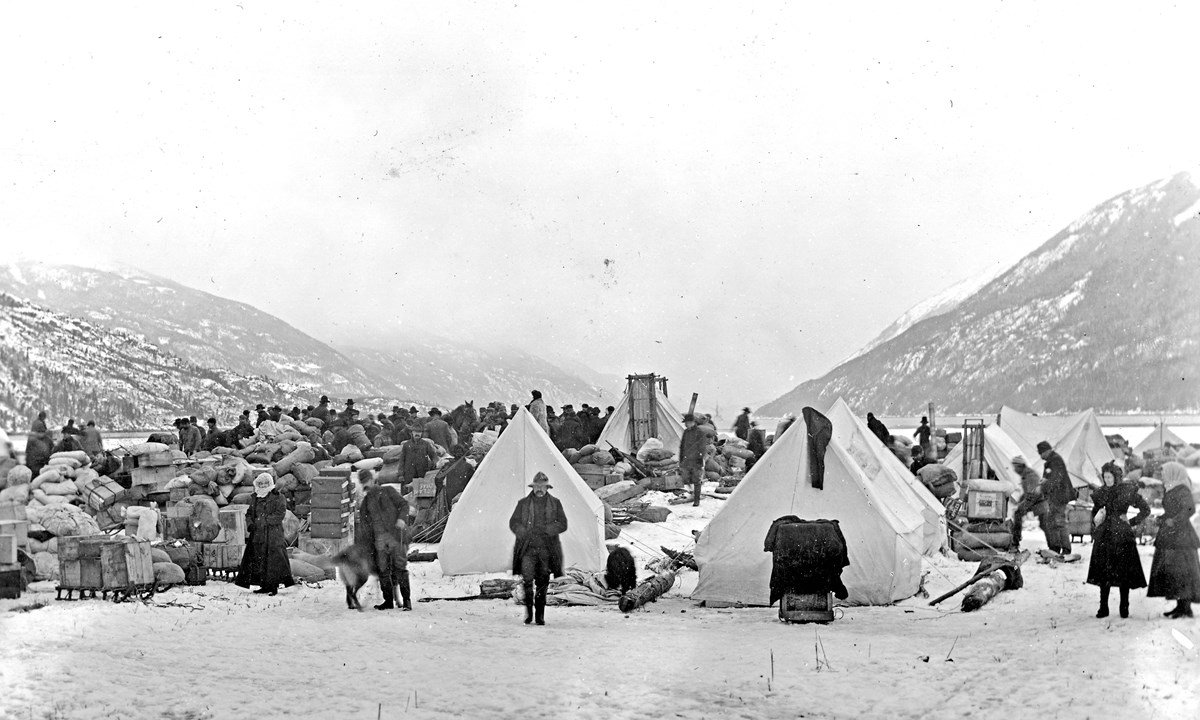

Archaeological Survey of the historic Dyea townsite, a National historic Landmark in Southeast Alaska.

A combination of human and natural forces has pushed the mighty Taiya River from the east valley wall into the historic Dyea townsite. Since 1947, the river has eroded 66 ft per year, but since 2017 the rate has greatly accelerated, with losses in 2021 totaling 116 ft. Dr. Flood is leading a team of National Park Service archaeologists on a mission to survey and inventory this heritage site of singular importance. Dyea was the landing spot for thousands upon thousands of hopeful prospectors eager for the Klondike goldfields and the chance to revolutionize their lives. Fall 1897 into Summer 1898 was the developmental explosion that transformed the Tlingit settlement in Dyea into a sprawling boomtown. Like most 19th century boomtowns, Dyea presented its immigrant population with an opportunity to remake American society, to enhance the elements of community they cherished and nullify elements, rules, behaviors they didn’t prefer. It was great a shake up. The town that bloomed from the seeds of chaos and desire now presents researchers with a rich landscape of opportunities. But whatever questions you might have, you better ask them now, because the river is relentless. Dyea and the network of sites along the Chilkoot Trail are likely the world’s premier repositories of material culture from the terminal Victorian Age, the Age of Wonder. Beyond the artifacts and features buried below the moss and eagles nests, Dyea holds fast the threads of “self-reliance” “perseverance” “adventure” and “personal transformation” that are tightly woven into the American identity.

Sicily’s lost Rivers and Inland Sea: Geoarchaeological investigations into human-induced erosion and progradation of the Catania Plain.

Since 2017, Flood has been working on a question very basic to the field of geography: why what is where. While working at the site of Morgantina, an ancient Greek marketplace and entrepôt, it occurred to Flood that the site makes very little sense as a commercial hub as it appears today. It is isolated deep in the interior of the island, high on a hill, and without a critical mineral or other resource to anchor populations there. Something must have been different in the past… and indeed it was. With the help of Alex Walthall, Tim Beach, and others, Flood is revealing that the parched and stream-less interior of Sicily was a riverine landscape when the Greeks pioneered the area in the 5th century BCE. Forest clearance and soil mismanagement clogged the once navigable harbors and slowly accumulated in the Catania Bay, turning the shallow inland sea into the fecund breadbasket and fruit-bowl it is today. This grant-funded research has been presented at numerous national meetings and will be published in two related peer-reviewed publications.

Ashlar Masonry & Monumental Architecture in Minoan Crete

Flood has been a member of the Mochlos Excavation Team since 2005. Since his first season with the dig, he has been fascinated by the large cut-stone blocks that allowed Minoan builders to produce soaring second and third story buildings with airy and spacious interiors. Where did this idea and technology originate? What did it take to produce these enormous orthostates? How far did they travel and why? Is this the beginning of the tradition of using large cut-stones in community architecture that we still employ today (e.g., The Washington Monument, the Texas State House, county courthouses)? Using XRF and microscopy, Flood and colleagues have linked the building blocks of Minoan Palaces with the quarries that produced them in the Bronze Age. In an upcoming publication (presented at the AIA meetings in 2020), Flood and colleagues show that Minoans found a high degree of cultural value in these large ashlar blocks and architectural forms they could produce, so much so that they were willing to haul them upwards of 20km over land and sea. Mapping the distribution of ashlar across the site of Mochlos using a dGPS instrument and AutoCAD software, Flood et al. have revealed the impetus for quarrying such unwieldy and resource-intensive large blocks of stone. More soon.

The archaeology and growth of plastic in Rural Environments

Plastics will be our archaeological legacy for those who bother to excavate what are sure to be the thick and colorful sedimentary layers of the 20th and 21st century. Plastic forks. Plastic straws. Plastic phones. plastic cars. Plastic jewels. Plastic crowns. Plastic legs. Plastic baby dolls. Plastic memory drives. Take a challenge. Go 24 hours without touching or using a piece of plastic. Where did this stuff come from, when did it arrive, and was it’s adoption slow and steady or did it take off like a plastic kite on a windy day? Flood has been digging at these question in what might seem like an unlikely place for answers: an abandoned coal company town in Appalachia. Yet, where else can one find a better sealed deposit than a town that opened in 1917 and was vacated on April 15th of 1950? In the sediments that fill the foundation of miner’s houses is the domestic material of rural American life. And guess what is there in abundance just after the second World War? Yep, plastic. In the middle of nowhere. Plastic. Flood’s research is showing through a unique lens that plastic charged into the American household and landscape like the Blitzkrieg many of the inhabitant of the coal town had just defeated. Plastic has dominated the assemblages of material from two seasons of excavation with FSU students. Plastic continues to interfere with geoarchaeological work Dr. Flood undertakes in Sicily and Greece. The spread of this material is most akin to the spread of bronze then iron in the great ages of civilization. But unlike bronze and iron, the items large and small will not readily dissolve into the environments where they lay. Even the lowly plastic knight will be in playable condition in several centuries. See (kemptonarchaeology.com) for more information.

Using Geochem to Source Ancient Ashlar

Building Palaces One Stone at A Time

Ashlar Blocks at Gournia

Plastic Knight from Kempton Excavations

“Σκαλί-σκαλί θα φτάσεις στην κορυφή.”

Greek Proverb

Published Work

Minoan Genius seal impression from Malia

Water Management in NeoPalatial Crete

How do societies respond to drought? Which of these responses has the potential to end up in the archaeological record? By combining the fields of Hazard Geography and Archaeology, Flood reveals that though water concerns imbued Minoan society during their final period (LM-I), their responses captured in the archaeological record indicate is wasn’t a pronounced drought that befell the island, rather a gradual yet noticeable decrease in precipitation and changing regional climate conditions. Large reservoir dams were constructed, fields mulched in ceramics fragments to lock in soil moisture, gutters hung, and cisterns dug and plastered. Even new creatures and ritual objects, like the libation-loving Minoan genius and the rain-calling sistrum were integrated into the fabric of Minoan culture. Read more in Flood & Soles article published in the journal Aegaeum (2014) or an extended version in Flood’s MA thesis: Water management in Neopalatial Crete and the development of the Mediterranean climate.

The many layers of past life at Kinet Höyük in S. Turkey.

The Chemistry of Human Sedentism: Geochemical work on Tells in Southern Turkey

When humans settle into a landscape, for whatever reason, be it agriculture, exploitable mineral resources, or perhaps it’s just so darn beautiful, they are forced to bring in essential materials from afar. Perhaps its building materials or a stone to grind grain against or timber to burn from a nearby glade. Traded items from more distant places have traditionally been one of the most exciting items for archaeologists to find. Yet, persisting long after the exotic olives, emmer, pelts, and even potential migrants themselves have melted into the sediments, their geochemical signature remains locked in the mineral matrix of the floors they sat on. With XRF and XRD, Flood and colleagues have revealed that human sediments can be detected from a chemical perspective, and furthermore that the elemental signature of human-sediments is remarkably consistent from the Early Bronze Age to today! In other words, when humans settled an area 4500 years ago they enriched the sediments they lived on with copper, mercury, and lead; then in the Iron Age, settlers on the same spot enriched the sediments they lived upon in copper, mercury, and lead; then in the Medieval the settlers atop these earlier deposits enriched their living surfaces in exactly copper, mercury, and lead. Today, we do a very very similar process. Think about the dust and microscopic materials in the corner of your living room, behind your stove, or on your front door step. Welcome home toxic elements, you are our an old old friend. Read more in (2017) Synthesis of geoarchaeological research around Kinet Höyük, Hatay, Turkey included in the Festschrift for the wonderful Marie-Henriette and Charles Gates.

Cambridge University Press: ISBN-13: 978-1107027930

Ancient Maya Water Management & Environmental Reconstruction

Galvanized in Shelley’s 1818 sonnet Ozymandias is urbanized society’s collective fear of returning to less nucleated and integrated times. Shelley expressed a fear of collapse that he recognized after witnessing the vestiges of bygone civilizations. Did these societies ever think they would cease to exist? Could this happen to 19th Century London? Can this happen to modern capitalistic global market-place constructed by billions of complex agreements and lines of transmission? Nah. Wait… maybe. This specter still haunts us now. Flood’s work in the Maya Lowlands looks at the role drought may have played in the disintegration of the Classical Maya commercial and social network. In a chapter published in Tikal: Paleoecology of an Ancient Maya City (2015), Flood and colleagues explore the adaptive water management approached employed by the ancient Maya and the superb environmental awareness to the hydro- and geosphere of their home habitat.

Lamania Maya site now under dense canopy.

The MayaCene

The Maya Lowlands today are characterized by low settlement density, poorly enriched soils, and often miasmic conditions. In a place that hosts so few humans today and endowed with such marginal soil resources, how did the ancient Maya develop large populations and cities to house and organize them? Read Flood and colleagues 2015 paper published in the journal The Holocene to find out more (‘Mayacene’ floodplain and wetland formation in the Rio Bravo Watershed of northwestern Belize.)

Hammerstone of rudist limestone from 3500 years ago. The right tool for the job is sometimes a round rock.

Stone Tools in the Age of Bronze

Flood has donned many hats on the Mochlos Excavation Project since 2005. A consistent item under his purview is the groundstone lithic assemblage. Though many people erroneously think the Bronze Age spelled the end of the stone age, lithic tools remained vital to the household and community functioning in the Bronze, Iron, and even into the early modern period. Stone provided the surface to process grain and fruiting bodies of plants that fed Minoan and later agricultural communities. Stones were the weights at the end of fishing nets that ensnared a major (and delicious) source of protein in the Minoan diet. Stones were the hammers that fastened the timbers in Minoan domestic construction and the anvil against which shells were cracked and opened. Sometimes stones were the talismans of some good fortune. Read more in Mochlos V: The House of the Metal Merchant and other Neopalatial Houses (2020) INSTAP Press.

Water Banking

How many of you reading this have ever sipped water from a plastic bottle? A better question might be: how many liters of water from plastic bottles have you consumed? Were those liters bottled from your local watershed? Probably not. Rather they were bottled and shipped from other watersheds around the world. Without realizing it, humanity has become akin to chaotic rain-cloud, a torrent tearing across watershed, a river valley diving toward a monetary base-level. In the Anthropocene we increasingly direct the transboundary flow of freshwater resources, not just in canalized streams but in bottled water, in water-rich fruits and vegetables, in soda and beer, and in packaged steaks and chicken legs. In Water Banking (2017), Luzzadder-Beach and Flood formalize this phenomenon by framing it under the term water-banking. Issues of physical and virtual water banking are explored in this brief but informative manuscript.

Population Growth & Water Quality Decline in Ancient Greek Cities

Flood, Walthall, and Buhagiar (2020) explore how ancient urbanites adapted to increasing levels of water pollution concomitant with population growth and density of human and livestock waste. Their research shows that water quality problems that plague nodes of concentrated human population also afflicted the Greeks and Romans. The ancients, however, diversified their approach to sourcing freshwater at a local scale. The ancient Greeks of Morgantina moved away from a total reliance on spring and well water as the aquifer below their town became polluted with nitrates, sulfate, and coliform bacteria of their own making. Small domestic cisterns and public collection basins were created to capture the pure rainfall. Water was captured and brought to the site through an impressive network of terra-cotta pipes. To cope with diminished overall quantities of groundwater that resulted from an expansion of impervious surfaces, Greek engineers in Sicily excavated qanats (horizontal well tunnels into an aquifer) to increase discharge and regularity of flow. What Flood and colleagues document at Morgantina are a host of human-hydrologic challenges that we still face today. The simple place-based solutions employed by the ancient Greeks may serve as local guideposts for adaptive water management behaviors today in central Sicily.

the most overlooked water Resource on the planet: Soil Water

It is both awesome and humbling to consider how much human effort and anguish has gone into soil water management… and how remarkable that so few of us think of it today. The great irrigation projects on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates, the millions upon millions of terrace walls clopped together stone by stone on hillsides across the planet, the chinampas that fed ancient Tenochtitlan, and the center pivot irrigation wheels that whirl around and around in central and southwest US to wet the ground just right for corn corn and more corn. Beach and Flood (2017) highlight this all-important water resource, it’s physical characteristics, its global distribution, mechanisms for its movement, and society’s relationship to it.

Wetland Hydrology

Jonathan’s specialty in the earth sciences is hydrology and water chemistry. He teaches courses in surface water hydrology at the undergraduate and graduate level, and as fun as the discharge calculations can be with fast moving systems, it when water slows down and lingers long that the biosphere seems to do the most with it (per liter). Where water pauses and soaks the pedosphere in a thin veneer, the great abundance of life in all the spheres seize the opportunity to interact and thrive. These zones of seasonal freshwater storage and flux have become the biodiversity hotspots the world over. Beach and Flood (2017) detail the mechanisms and functions of wetland formation through the science of hydrology. They connect these areas across the planet to the unique hydrologic conditions present and conclude with an earnest appraisal of wetland’s future outlook in the unfolding Anthropocene.

The Maya Tropical forest is a gallery of sounds, smells, textures and mosquitoes.

The Paleoecology and Geoarchaeology At El Palmar and El Zotz

In an article published in the Journal Geoarchaeology, Flood and colleagues (2016) use environmental proxy data recovered from sediment cores collected from infilled water reservoirs in the Peten to reconstruct past floral assemblages and reconstruct past climatic conditions. This paper is significant in several ways: 1) it shows a glimpse of the pre-disturbance landscape prior to Ancient Maya land clearance; and 2) captures the long and steady augmentation of the natural landscape from the Archaic to the Late Classic. Flood’s most direct contribution to the article was determining the percentage of soil organic carbon (SOC) derived from C4 plants versus C3 species using δ13C profiles. Zea maize is a C4 plant, and it indeed spikes during known periods of Maya disturbance and population growth, but interestingly the C3 species remained the majority at each level in the sequences. This suggests that Lentz (2015) was perhaps correct in suggesting that the ancient Maya didn’t go out and clearcut the forest to cultivate, rather the forest was part of the agricultural mosaic of the region.

.

Architectural Stone at Mochlos

Block by block community identity was woven into the architecture at Mochlos and other population centers across Bronze Age Crete. In Mochlos V: Architectural Stone, Flood (2020) explores the size, fabrication, use, and transport of cutstone blocks from the Neopalatial quarry at Mochlos with XRF, microscopy, and gps mapping of their distribution across the site. These large orthostates represent an enormous community investment, complex cooperation, and a striving for cultural inclusion byway of emulating architectural elements already in use at larger Minoan “Palatial” centers.

Assorted scenes from the field.

Contact Dr. Flood

—

CV